Alongside remains of the most ancient civilizations on earth, texts declaring the divine nature of figs have been discovered. From as early as 2334 BCE, clay Akkadian tablets extensively describe the role of figs in Mesopotamian society. According to administrative texts from the Sargonid and Ur dynasties, strings of fresh and dried figs were sold as “food for the commoner, as well as for the gods.”1 Commoners, people without rank in these ancient civilizations, could purchase twelve to fifteen strings of figs for one shekel of silver; a month's worth of income. A price worth paying for a chance at divine favor.

Figs, alongside raisins and wine, were common offerings to Šamaš (Shamash), the sun, and other deities because they were believed to “quiet the hearts of the gods.”2 As keepers of the cosmos and creation, Mesopotamian gods were venerated during daily rituals, in addition to larger monthly festivals that sometimes lasted multiple days. Figs, dates and raisins were offered as sacrifices at meals. These fruits were also the ingredients of Qullupu, fruitcakes that were gifted to the gods during festivals.3 Additionally, figs were utilized for their medicinal properties. Among the ruins of Ugarit, an ancient city in modern day Syria, excavated medical texts describe the use of old fig and raisin cakes and grout flour as a remedy for horses.4

Osiris Unas, take the breast of Horus, which they taste!

Two baskets of figs.

Pyramid Texts of Unas (2660 to 2181 BCE)

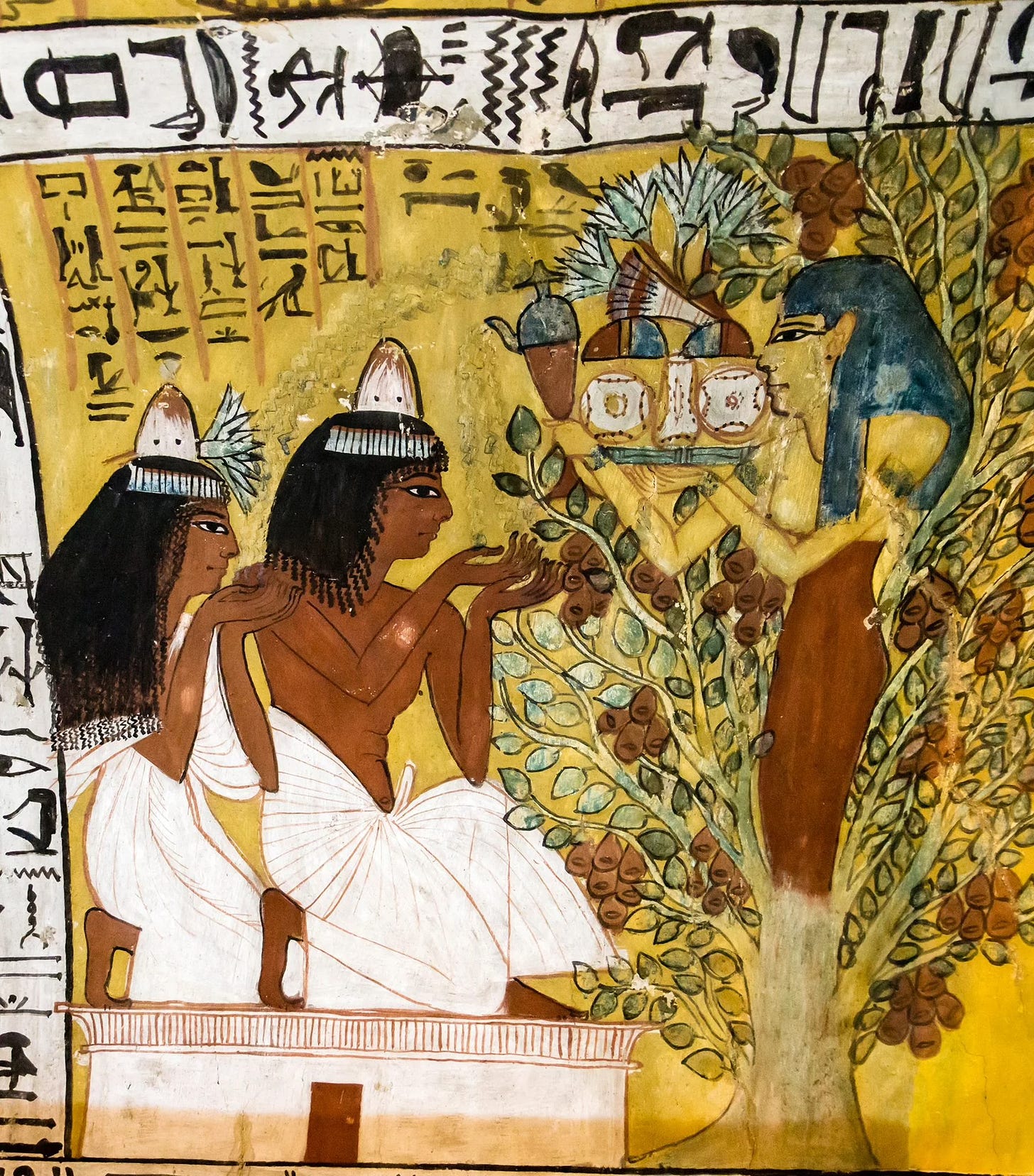

In the Pyramid Texts, funerary texts of Ancient Egypt, figs and wine are revered as the “food and drink of heaven.”5 Paintings of Egyptian gardens and orchards, on the walls of the pyramids, include fig trees. Ḥwt-ḥr (Hathor), goddess of the sun, and Nwt (Nut), goddess of the sky, are both depicted in tomb paintings from 2700 to 1100 BCE as Sycamore fig trees. More than common fig trees, Sycamore fig trees were cherished throughout the lands of Egypt for their food and shade. For this reason, Hathor was lovingly known as the “Mistress of the Sycamore” and Sycamore fig trees were considered the meeting place for lovers.6

In the Hebrew Bible, the fig, fig leaf and fig tree are referenced twenty-one times in different genres and contexts. One of the most popular instances is the forbidden fruit of Genesis, which many scholars agree was most likely a fig because later in the narrative Eve and Adam are said to have covered themselves with fig leaves (Genesis 3:7). In this creation myth, figs represent a pathway to divinity. The text also indicates the importance of figs as food and medicine in Ancient Canaan. As such figs are frequently employed as a metaphor for wellness, prosperity and peace.7 In 1 Samuel 30:12, the young Egyptian man, found starving in the desert, is revived in spirit with fig cakes, raisins, bread and water. In the Ancient Near East, medicine and magic were synonymous. Therefore, this passage indicates an association between figs and spiritual health, in addition to physical well-being. In the erotic poetry of Song of Songs, the start of Spring is associated with the blooming of fig trees.

The fig tree puts forth its figs,

and vines are in blossom;

they give forth fragrance.

Arise, my love, my fair one,

and come away.

Song of Songs 2:13

During the Greco-Roman period (332 BCE to 180 CE), figs were still associated with the divine. Plutarch, a Greek philosopher and priest of Apollo at Delphi, wrote that figs and honey were eaten to honor Hermes, a Greek rendition of Ḏḥwtj (Djehuty), the Egyptian god of the moon, reckoning, wisdom and writing. In this context, eating figs and honey was understood to be a declaration of truth.8 Greek poet Archilochus explores the relationship between figs and the land and works with fig metaphors in his writings.

Wild fig tree of the rocks, so often the feeder of ravens,

Loves-them-all, the seducible, the stranger’s delight.

Archilochus (680 to 645 BCE)

From the many ancient healing properties of figs, the Mesopotamian belief in their ability to quiet the hearts of the gods continues to provide us with potent wisdom. In a world that encourages endless longing and aimless ambition, the fig reminds us that even the creators of the cosmos must choose to embrace satisfaction and stillness. The same way God marvels at their work, declares it good and chooses to rest, we must appreciate our miraculous ability to create and rest to preserve it (Genesis 1:31). We must remain present in the space between being and non-being. We must move with the utmost respect for our creativity, for our holy work of merging the mysterious and the material. As Imago Dei, images of God, figs inspire us to rest and remember that we are divine.

Nili S. Fox, “Fantastic Figs in Jeremiah’s Baskets and in the Ancient Near East,” Proceedings 22 (2002): 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 99.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 101.

Fox, “Fantastic Figs,” 100.